The Importance of your data model

One of the key lessons I’ve learned while working on barkeep is the importance of getting your fundamental data models right. In this post I’m going to walk through the different major data model evolutions that barkeep has had, and reflect on each.

The first model: Incredibly Basic

I started this project with just a few basic requirements:

- A way to track the specific bottles in my collection

- Recipes which collect specific (or so I thought at the time) “required bottles” and the amounts necessary for each drink.

- Some link between the bottles in recipes and the bottles in my collection

I imagined my application full of recipes like this:

Drink Name: Last Word

Required Amounts:

- 0.75 oz of Gin

- 0.75 oz of Maraschino Liquor

- 0.75 oz of Green Chartreuse

- 0.75 oz of Lime Juice

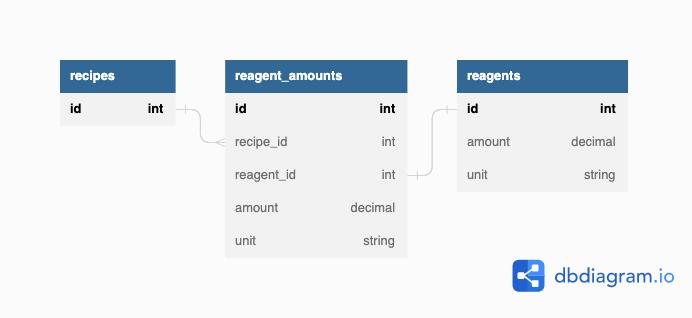

Immediately one can see challenges with modeling this recipe, but in the interest of establishing an “MVP” as soon as possible, I charged ahead to create a simple database schema that could represent it. We can visualize the schema I came up with below:

This is the absolute simplest thing I could have made, but it got the job done assuming I could get data into it. Rails would allow me to search through the reagent_amounts for reagents which matched, and which had enough available volume, and I’d be off to the races.

However, I ran into issues almost immediately with the inflexibility of this approach. First of all, just loading data into this data model wasn’t pleasant, since I had to find the right reagent_amounts.id’s while creating reagents. Then, if reagents ever needed to change, or especially be modified in bulk, I knew I’d be iterating through reagent_amounts non-stop with a major mess on my hands.

Most importantly, this data model makes it very difficult to actually represent the complexity of liquor bottles and cocktail recipes. The Last Word recipe above hints at this, but let me explain even further.

The complexity of cocktail recipes

Cocktails recipes, on the whole, are a confusing combination of some specific instructions and some highly generic information. A Last Word must have Green Chartreuse, of which there is only one kind in the world. No one other than a certain sect of monks in France are allowed to make it. Gin, however, is a massive category of spirits with some dramatically different flavor profiles. There’s London Dry Gin (a category unto itself), Sloe Gin, Plymouth Gin, Old Tom Gin, the list goes on! And that’s only one cocktail!

My data model needed to evolve to handle this complexity if it was ever going to work.

The second model: Enter the Category

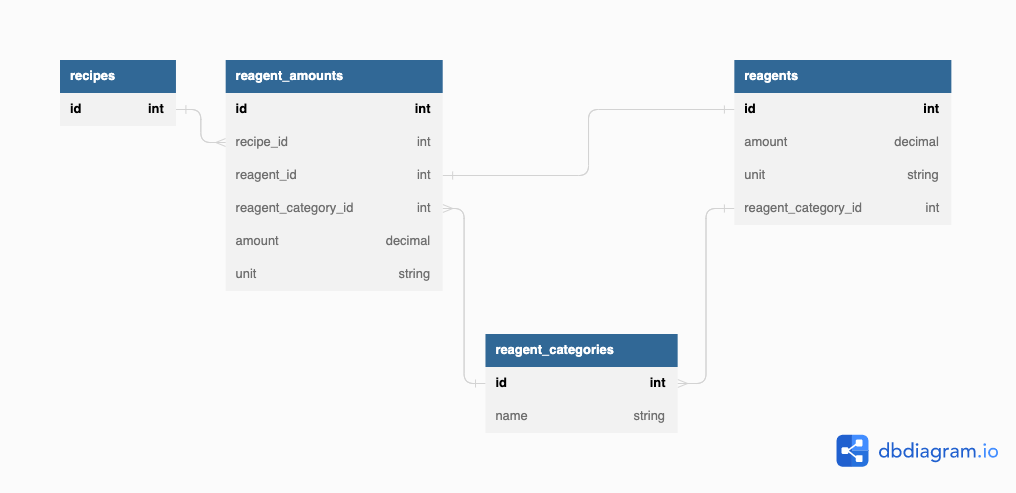

With these new complexities in mind, I opted to deepen the data model with an intermediary layer: categories.

Categories sat in between the cocktail’s required reagent_amounts and the bottles in my collection by serving as a join table of sorts. I attempted to model the complexity of each cocktail recipe by allowing a required “amount” to reference either a particular bottle or a category, which I hoped could handle the Green Chartreuse vs Gin conundrum.

This data model actually worked for me for a time, and I was able to make a decent amount of progress on the other parts of the app with it in place. At this point I could prove out the starting principles of barkeep and actually had a working implementation of the original goal: tell me what drinks I can make right now.

With the growing capabilities of the app, however, came new feature ideas. I had realized at this point that I needed to put the app on the internet, which required that I add user_ids to each of my models. That realization was driven by my desire to be able to take the app on the go, to my local liquor store, and use it to scout out bottles that would unlock new recipes. In order to do that easily, I needed to be able to automatically link a new reagent to all of the recipes that use it, and that became the straw that broke this camel’s back.

The issue with this data model was the strong linkage required between each model. A recipe might require Batavia Arrack (one of those particular spirits, like Green Chartreuse), which I might not own yet. If I went to the store, bought a bottle, and wanted to add it to my collection of reagents, under the hood I had to iterate through each recipe’s required amounts, find each reference to Batavia Arrack, and link that amount with my new reagent. This is equally bad on the deletion side because amounts needed to be unlinked from the now deleted reagents so that recipes didn’t error out when being queried from ActiveRecord. Astute readers will recognize that this was basically the same set of problems I had with the first data model, and all I’d really done was add complexity without solving problems.

So, it was time for the next data model.

The third model: All in on Categories

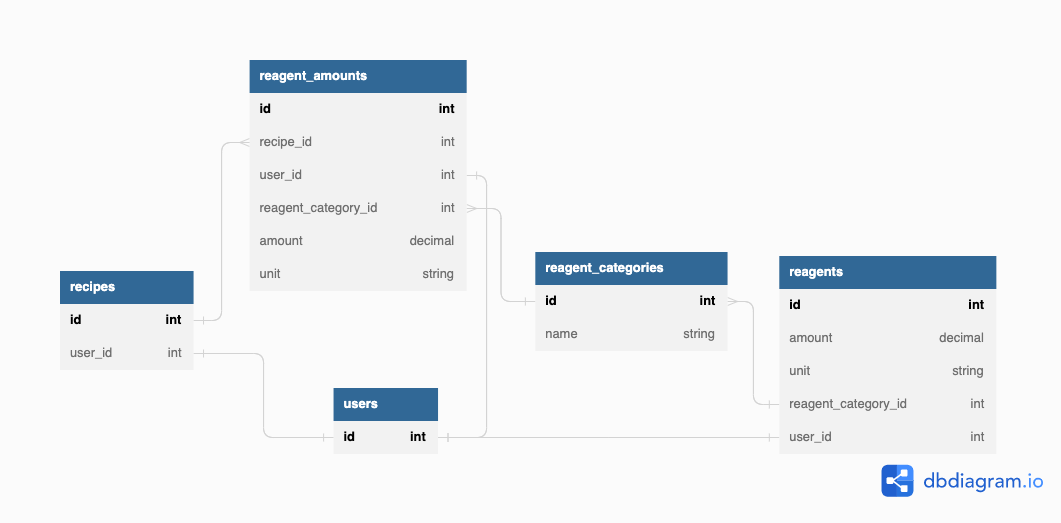

At this point, I realized I should just lean in fully on categories, giving each required amount a category even if it would only ever link to a single type of reagent. The layer of indirection provided by this decision would enable a lot of future development, and actually serves as a hint towards the next (and current, at the time of writing), data model.

For now, however, we just had the following:

Users existed at this point, which created the additional wrinkle that I had decided categories should be globally unique across users, while every other model had user_ids associated with them. I had started to have ambitions around sharing a list of recipes between all users, as well as allowing users to create their own private cocktails, and being able to link recipes to a global list made that sharing easier to conceptualize.

The essential benefit of this change was that it started to weaken the links between a recipe’s required amounts and specific user bottles. Since ReagentCategories sat in between ReagentAmounts and Reagents, I only had to get that linkage correct in order to have working models.

Like before, I was able to make solid progress on other parts of the app at this point. The data model was finally in a place where I could figure out user logins, audits, and other small features without feeling stuck on my current model.

Despite those improvements, with enough time a similar tune from before began to play: I had features I wanted to add, and the data model was starting to hold me back yet again. This time, it was two things:

- I was still juggling specific relationship ids in ways that felt unpleasant. Copying recipes from the new “shared” space (recipes with a

niluser_idare considered shared) involved copying lots of specific foreign keys. Correcting a duplicateReagentCategorymeant finding all the recipes linked to it and relinking them to the correct new model. It felt fragile, which limited my interest in building more complexity on top of it. - I realized recipes are occasionally even more complex than described above, and are easiest to use if they allow multiple categories to fulfill their requirements. Sometimes a drink can be made with Gin or London Dry Gin, but never Old Tom Gin (or other wacky gin types). I needed to have a single amount refer to multiple categories, and I wanted it to be easy for users to re-categorize cocktails on the fly.

Then, while in conversation with a coworker about this data model, he struck on an even better way to link recipes: “tags”. With my own satisfaction dwindling, and a new idea burning a hole in my brain, it was time for the fourth data model.

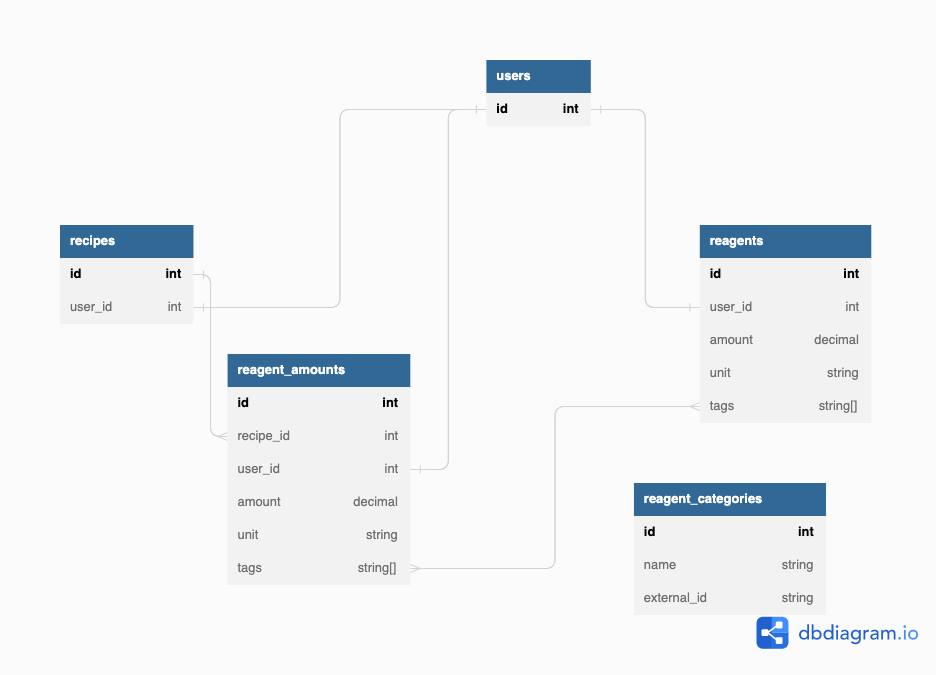

The fourth model: Tags

The essential element of this latest data model is the softening of the linkage between the recipes and amounts side of the house, and the categories and bottles that user’s possess. This “softening” was done by converting the linkage between the models from direct foreign key ids to lists of “external ids”, or tags. This is harder to model visually, but a rough diagram of the current model is below:

The diagram does a poor job of describing how this works, but in brief:

ReagentAmountshavetags, which are a set of snake case “external ids”, really just strings that we make sure conform to some simple rules.- User

Reagentsalso have a list oftags - All

tagsare sourced fromReagentCategories, which is a globally unique list of the different possible tags. - When searching for recipes that can be made, we just do set intersections between the set of

tagsa user has (all the tags across all their reagents), and the sets of tags belonging to eachrecipe. If an intersection isn’t empty, that means the user can probably make the drink.

This model makes it trivial to “link” new recipes together with the bottles in a user’s collection, because as long as they use the same tag, they have a relationship. I don’t need to actually setup direct linkages between rows in the database, but can instead rely on the query patterns to ensure things are found. Copying cocktails between users is easy now, as is providing a better experience for creating new recipes. Correcting incorrect recipes just requires changing the spelling of specific tags, and the links appear automatically.

I debated setting up this data model for a long time before I actually did it, and even tried to implement it once before giving up and coming back to it a month later. What stopped me the first time was the usual culprit in these situations: premature optimization. I was worried that I couldn’t write efficient queries against these tables since they would no longer be easily indexable foreign keys. (This was obviously premature because my current production database has around 225 total recipes. What was there to be afraid of?).

I did finally get around to it though, and once I had this data model in place the biggest impact was actually felt elsewhere in the project, in all of the new features I’ve been able to quickly iterate on. That, I think, was the real lesson in all this work.

Conclusions

Data models are so many things to a project. They’re storage, they’re access patterns, they’re operational concerns. But above all else, they’re the UX of your own ability to develop the application. Each of these data models unlocked new features that I was now able to build, because they reduced the time my brain would have to spend maintaining the data model itself.

The final challenge, however, is that each of these conversions took me a lot of time, and while they were underway I felt like I couldn’t make any progress on other features. As I look to the future, I need to consider the two costs of each model: the cost of not implementing it, which will reduce my own developer UX, and the cost of actually implementing it, and spending weeks+ wrangling the project back to normal.

The future

This post is already long, so I’ll save a deep dive into future data models for another post. However, there are some things already bothering me about data model #4, and eventually I’ll reach the activation energy required to change it yet again.

- I’ve hand rolled service objects to avoid N+1 queries, which has worked fine so far, but it means I’m not leaning into the existing ActiveRecord tools that could probably traverse these relationships for me

- I’m not sure it’s worth having separate

reagent_amountmodels. I could probably just move the tags into blobs on therecipemodel itself. The separate models are really just a hold out from the first data model anyway. - Doing the above would unlock faceting via PG, which I think is a feature I’ll want pretty soon.

We’ll see what comes next, but whatever it is, I hope my data model is ready for it!

Last week’s post: Forever 1% Better

Next week’s post: Is your front end running? Better go catch it